As students of yoga, most of us are familiar with the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali which is considered to be the most authoritative text on the underlying concepts of yoga. It deals with the human mind, how it functions, why we go through suffering, and how to cleanse/purify the mind so we can eliminate suffering and attain self-realization. Many of the concepts discussed by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras are known to have as their basis some of the basic tenets of another philosophical system called Samkhya. In the discussion below, wherever applicable, I will try to correlate the themes presented here with the corresponding ideas in the Yoga Sutras.

Samkhya is one of the six systems of Indian Philosophy (Shad-darshana). A brief listing of these six systems is given below:

- Nyaya: A system of logical realism, founded by Gautama, known for its systems of logic and epistemology and concerned with the means of acquiring right knowledge.

- Vaisheshika: Philosophy founded by Kanada teaching that liberation is to be attained through understanding the nature of existence, which is classified in nine basic realities (dravyas): earth, water, light, air, ether, time, space, soul and mind. Nyaya and Vaisheshika are viewed as a complementary pair, with Nyaya emphasizing logic, and Vaisheshika analyzing the nature of the world.

- Sankhya: A philosophy founded by the sage Kapila, author of the Sankhya Sutras. Sankhya is primarily concerned with the “25 categories of existence/evolution – tattvas” . The first two are purusha and primal nature, prakriti—the dual polarity, viewed as the foundation of all existence. Prakriti, out of which all things evolve, is the unity of the three gunas: sattva, rajas and tamas. Sankhya and Yoga are considered an inseparable pair whose principles permeate all of Hinduism.

- Yoga: The tradition of philosophy and practice codified by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras. It is also known as raja yoga, “king of yogas,” or ashtanga yoga, “eight-limbed yoga.” Its object is to achieve, at will, the cessation of all fluctuations of the mind, and the attainment of Self Realization.

- Mimamsa: Also known as Purva Mimamsa. Founded by Jaimini, author of the Mimamsa Sutras, who taught the correct performance of Vedic rites as the means to liberation.

- Vedanta: Also, known as Uttara Mimamsa: “End (or culmination) of the Vedas.” For Vedanta, the main basis is the Upanishads and Aranyakas (the “end,” anta, of the Vedas), rather than the hymns and ritual portions of the Vedas. The teaching of Vedånta is that there is one Absolute Reality, Brahman. Man is one with Brahman, and the object of life is to realize that truth through right knowledge, intuition and personal experience. The Vedanta Sutras (or Brahma Sutras) were composed by Rishi Badarayana.

Basic tenets of Samkhya philosophy

Samkhya is regarded as the most ancient of the Indian Schools of thought. Some scholars believe that it even pre-dates the Vedas. Even though Kapila is considered to be the original founder of Samkhya and the author of “Samkhya Sutra”, many believe that the version of his text available today may not be authentic or original. Currently, the text that is widely studied as the original text on Samkhya is “Samkhya Karika” by Ishwara Krishna. The basic aim of Samkhya, as given in the very first verse of the Karika is to eliminate the three-fold “dukkha” (suffering):

- Ādhyātmikam (internal)

- Physical – caused by the imbalance of the doshas – vata, pitta, kapha; fever; physical pain

- Mental – separation from loved one; inability to get rid of object of dislike; six enemies (shad-ripu) – lust, anger, greed, infatuation, arrogance, jealousy; fear; grief etc.

- Ādhibhautikam (external) – caused by man, beast, birds, reptiles, plants and other inanimate objects

- ādhidaivikaṁ (divine) – cyclone, tsunami, fire, plague, flood, famine etc.

Some of the main themes that are presented in the Samkhya philosophy are:

- Theory of causation (satkaryavada)

- Concept of duality, two independent entities: Purusha (the consciousness principle) and Prakriti (non-conscious principle)

- The theory of evolution of the material universe (25 elements, called “tattwas” – Purusha, Prakriti and 23 evolutes)

- The concept of liberation (moksha, kaivalya)

- Theory of knowledge (pramana)

- Concept of the three gunas – sattva, rajas and tamas

Let’s take a brief look at these concepts.

Theory of cause and effect (Satkaryavada)

Satkaryavada is one of the main concepts presented in the Samkhya philosophy. According to this theory, the effect is already pre-existent in the cause. For example, milk being the cause, its effect yogurt pre-exists in the milk. Based on a certain specific trigger, the effect gets manifested from the cause. This principle of manifestation from cause to effect is termed as “parinamavada” in Samkhya. The philosophy of evolution of all aspects of this material universe as given in Samkhya is based on this principle.

Principle of duality – Purusha and Prakriti

As per the Samkhya system, this universe of animate and inanimate object is the creation of two distinct, independent entities called Purusha and Prakriti. Both these entities are eternal and real. Purusha is pure consciousness whereas Prakriti is the primordial material entity, which has no consciousness of its own. The universe gets manifested from the unmanifest Prakriti through the proximity and conjunction between Purusha and Prakriti. As mentioned in the Samkhya Karika (SK 20), the two work together just as a lame person and a blind person would help each other to arrive at their destination. Having reached the destination, they part ways and become independent of each other. That final state of freedom from each other is termed “Kaivalya” both in the Karika as well as the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (for example, sutra 4.34).

In the Yoga Sutras, the concept of duality (Purusha and Prakriti) is discussed in many of the sutras, both in chapter 2 and chapter 4. For example:

- Egoism (asmita) is the identification, as it were, of the power of the Seer (Purusha) with that of the instrument of seeing [intellect and the rest] (sutra 2.6)

- The cause of that avoidable pain is the union of the Seer (Purusha) and the seen (Prakriti, or Nature) (sutra 2.17)

Purusha

Samkhya Karika describes the individual Purusha in a variety of ways in multiple verses – un-caused; neither produced nor does it produce; attribute-less; absolute; infinite; all-pervasive; inactive; solitary; unsupported; non-emergent; not made of parts; independent; witness only, isolated and free (kaivalya); non-doer (akartrbhava); consciousness (chetana); a free, action-less witness.

In most translations, it is usually referred to as “pure consciousness”. In common parlance, Purusha is usually translated as the soul, atman, the Self etc.

Since Prakriti has no consciousness of its own, it uses the reflected consciousness from Purusha so that the intellect, mind, ego and the senses can perform their respective functions.

Samkhya also establishes the multiplicity of Purushas. Each individual living entity being its own Purusha. Prakriti is presented as being common to all Purushas.

The concept of Purusha appears in a large number of Patanjali Yoga Sutras. For example, see sutras 1.3 and 2.20. In these sutras, Purusha is referred to as (drashta) or the “seer”.

- Then the Seer [Self, Purusha] abides in His own nature (sutra 1.3)

- The Seer (Purusha) is nothing but the power of seeing which, although pure, appears to see through the mind (sutra 2.20)

Prakriti

Prakriti, in its unmanifest form (usually called Mula Prakriti or Pradhana) is independent, uncaused, eternal, and all pervading but has no consciousness of its own. It is the cause of this material creation. However, for creation, it uses the proximity and conjunction with Purusha whose consciousness gets reflected into Prakriti to help with the creation.

Patanjali provides a nice definition of Prakriti in sutra 2.18:

- “The seen (Prakriti) is of the nature of the three gunas: illumination (sattva), activity (rajas) and inertia (tamas); and consists of the elements and sense organs, and its purpose is to provide both experiences and liberation to the Purusha.” (Sutra 2.18)

The three gunas (sattva, rajas and tamas)

Everything in this material universe is a composite of three gunas – sattva (purity), rajas (action) and tamas (dullness). The unmanifest Prakriti is nothing but the combination of these three gunas present in a state of perfect balance or equilibrium. Samkhya Karika, however, gives no indication as to what this “perfect balance” implies. At some point in time (we can call it “time t = 0”), due to the proximity between Purusha and Prakriti, this balance is disturbed in favor of rajas and the dominance of rajas leads to the evolution of this material world, including the human being. This state of imbalance which leads to evolution is termed Vikriti. The gunas should not be considered as qualities or attributes of Prakriti but as its very form itself.

Even though at times the gunas may seem antagonistic to each other, they normally work in cooperation with each other. As per SK 13:

“Sattva is light and illuminating, rajas is exciting and restless, and tamas is heavy and enveloping. They work in conjunction with each other just like oil, wick and the flame work together in a lamp to create light.”

An intrinsic quality of the gunas is that they are always in a state of constant flux. If one of the gunas, say sattva, is dominant at a given instance of time, at the very next moment one of the other gunas, rajas or tamas may assume dominance.

It’s these gunas that are responsible for developing raga (attachment) and dvesha (aversion) in humans which propel one to action. These actions which can be punya (good or benevolent), apunya (bad or evil) or a mix of these two, result in this perpetual cycle of birth, death and rebirth (called “samsara”).

Gunas are mentioned by Patanjali in many sutras:

- When there is non-thirst for even the gunas (constituents of nature) dues to the realization of Parusha (true Self), that is supreme non-attachment (sutra 1.16)

- Thus, the supreme state of Independence (kaivalya) manifests while the gunas reabsorb themselves into Prakriti, having no more purpose to serve the Purusha. Or to look from another angle, the power of pure consciousness settles in its own pure nature (sutra 4.34)

Theory of evolution

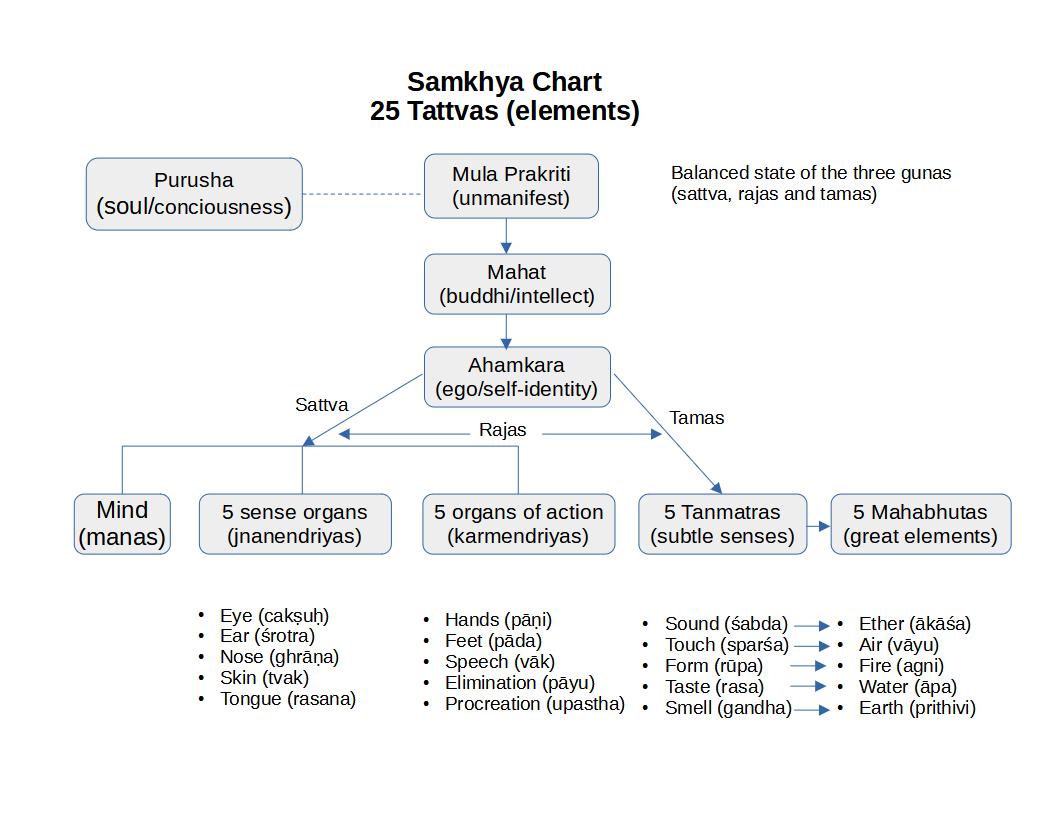

25 tattvas (elements) in Samkhya

The process of evolution as given in the Samkhya is one of its most fascinating contributions. As stated above, evolution began when the perfect balance of the three gunas in the Mula Prakriti was disturbed, resulting in the evolution of the 23 elements (tattvas) given here. The first evolute that appears as a result of this “vikriti” (mutation) is mahat or buddhi (intellect). From buddhi evolves “ahamkara” (ego), the individual principle. From ahamkara, the dominance of sattva guna results in the evolution of 11 indriyas or sense perceptions. These are:

- Five jnanendriyas (organs of knowledge or perception) – the eye, the ear, the nose, the skin and the tongue

- Five karmendriyas (organs of action) – hands and arms, feet and legs, tongue for speech, organs of elimination and organs of procreation

- Manas (mind) that supports both the organs of action as well as the organs of perception

Also, from ahamkara, the dominance of tamas guna results in the evolution of the five tanmatras (the subtle sense perceptions) – the senses of touch, smell, taste, vision and hearing. From these five tanmatras evolve the corresponding five “mahabhutas” (the great elements) – earth (smell), water (taste), fire (vision), air (touch) and ether (hearing).

When we add the Mula Prakriti and the Purusha (pure consciousness) to these 23 elements, we get a total of 25 elements (tattvas). In essence, then, we as individuals are a composite of these 25 elements.

In sutra 2.19, Patanjali makes an oblique reference to these tattvas. He defines the stages of the gunas as:

- specific (vishesha)

–Five gross elements – earth, water, fire, air, ether

–Five sense organs – ears, skin, eyes, nose, tongue

–Five organs of action – hands, legs, speech, excretion, procreation

–Mind

- non-specific (avishesha)

–Ahamkara (ego)

–Five tanmatras (subtle elements) – smell, taste, form, touch, sound

- with indicator only (linga-matra) – intellect

- without any indicator (alinga) – unmanifest Prakriti

Concept of liberation

As stated earlier, Samkhya recognizes that we are always dealing with three types of suffering. Even what may seem pleasurable for the time being will ultimately result in disappointment and suffering. The reason for this suffering is our ignorance – we are not aware of our true nature. We are constantly identifying ourselves with the mind-body complex which results in the perpetual cycle of birth, death and re-birth.

The way to overcome this suffering is to develop a pure discriminatory wisdom (viveka) which will lead to the state of complete freedom (kaivalya). In this state Purusha, who is free from any limitations of space, time and causation, is no more entangled with Prakriti and the intellect (buddhi) has become fully aware of this separation. This is termed as liberation or self-realization.

Samkhya recommends a process of involution – going from the gross back to the subtle-most element, finally merging with Mula Prakriti or the unmanifest Prakriti. This process has been termed as “prati-prasava” (going back to the womb) in both Samkhya and the yoga sutras. It is stated in SK-64, “Through the practice of the 25 tattvas (elements) and realizing the truth, one attains the wisdom of “I am not”, “nothing belongs to me” and “not-I”. This wisdom is free of any misconception, is pure and leads to the knowledge of absolute truth.”

In essence, to attain liberation, we need to reverse the path described above for the process of evolution. As described there, evolution begins at the Mula Prakriti level, and goes through buddhi (intellect), ahamkara (ego), mind, the five tanmatras (sense perceptions) and finally all the indriyas (11 senses) and the 5 great elements. The involution process is just the reverse – one starts by contemplating on the gross elements. Then, moving up the chain, one goes through contemplation on the five tanmatras, ego and the intellect. When the intellect is purified and the ego has been completely subdued, the final state of self-realization is reached.

Pantanjali, in the Yoga Sutras, talks about the attributes and characteristics of both Purusha and Prakriti, as well as the roles they play. As defined in sutra 2.18, Prakriti has two roles to perform – bhoga (experiencing life) and apavarga (liberation).

Sutra 2.18

prakāśa-kriyā-sthiti-śīlaṁ bhūtendriya-ātmakaṁ bhoga-apavarga-arthaṁ dr̥śyam ॥18॥

The seen (Prakriti) is of the nature of the three gunas: illumination (sattva), activity (rajas) and inertia (tamas); and consists of the elements and sense organs, whose purpose is to provide both experiences and liberation to the Purusha. (Sutra 2.18)

Prakriti presents all life experiences to the Purusha either as a result of perception through the five senses, or by bringing up thoughts, feelings and emotions based on memory. Through practice of yoga, buddhi (intellect) begins to realize that to eliminate suffering, it needs to allow Purusha to let go of the bondage with prakriti. The realization that Purusha and Prakriti are independent entities, is termed as Kaivalya (liberation).

As mentioned earlier, Patanjali describes the final state of liberation (kaivalya) in sutra 4.34.

Theory of knowledge

Samkhya acknowledges three sources of valid knowledge:

- direct perception (drishtam)

- inference (anumana)

- valid testimony (apta-vachana).

Sutra SK-4 states, “Perception, inference, and valid testimony are the sources for establishing all correct knowledge. Through these three, any knowable object is completely known.”

Direct perception is attributed to the five sense perceptions – touch, taste, smell, sight and hearing. Of course, the mind (manas) and the intellect (buddhi), being a part of Prakriti, do not have consciousness of their own. They need the reflected consciousness from the Purusha to perform any of their functions, including processing of perception through the five senses.

Inference (anumana) is dependent on something that has been experienced in the past based on direct perception. There are three categories of inference:

- Purvavat – when an inference is made from a perceived cause about an effect that is yet to come. For example, future rain is inferred by seeing thick, dark clouds.

- Sheshavat – when an inference is made about the cause of something perceived at the present moment as the effect. For example, recent rain is inferred by the sight of fast flowing, muddy river water.

- Samanyato-drishtam – when inference is made from something that is commonly known. Inference of fire by seeing smoke on a distant hill is a common example of this category.

Patanjali, in the Yoga Sutras, also defines the same three categories of valid knowledge:

- The sources of right knowledge are direct perception, inference and scriptural testimony (sutra 1.7). However, he uses different Sanskrit terms than used in the Karika for direct perception (pratyaksha) and valid testimony (agama).

Concluding remarks

In this discussion, I have attempted to provide a brief overview of the basic concepts presented in the Samkhya philosophy. The objective of Samkhya is to eliminate the three-fold suffering as given above. This suffering is caused by our ignorance (avidya) which makes the Purusha identify itself with the mind-body complex (Prakriti). Elimination of this suffering is achieved through a realization of the separation between Purusha and Prakriti. Samkhya presents the concept of evolution of this material world into 23 elements.

As mentioned earlier, Patanjali, in his yoga sutras, has used many of the Samkhya concepts as a foundation for his yoga philosophy which he develops as a practical guide for the attainment of the goals of yoga. Patanjali also introduces the principle of Ishwara (God) which he defines as a “special Purusha” which undergoes no change caused by afflictions or karma etc. He recommends “Ishwara pranidhana” (surrender to Ishwara) as a means to achieve the state of “samadhi” which will lead to final liberation. As a practical approach to yoga, he presents the eight limbs of yoga (Ashtanga Yoga) as the means to attain a pure, discriminatory wisdom which will ultimately lead to final liberation (kaivalya).

beautiful article.

Thanks.

Many of my doubts are clarified. Thanks.

Thanks. I am glad you found it useful.

The article is very helpful.

thanks for the kind feedback.

[…] or enable JavaScript if it is disabled in your browser. Sankhya Darshanam …Overview of Samkhya Philosophy | Yoga With Subhashhttps://yogawithsubhash.com › 2020 › Apri…27-Apr-2020 — Sankhya: A philosophy founded by the sage Kapila, author of […]

Great article Sir. I keep reading this again and again when questions arise in my mind. Many thanks 🙏

Thanks, Deepa, for your kind feedback.

A great work. thank you, sir. Can you explain more about asmita in yoga please?

Patanjali uses asmita in two different contexts. In sutra 1.17 he uses asmita to represent the highest state of samprajnata samadhi – the essence of pure being. In chapter 2, sutra 2.3, he lists asmita as one of the five kleshas. Here it represents the negative ego which causes raga and dvesha leading to suffering

Subhashji, so beautifully explained and summarized. Samkhya darshan explained in such crisp and simple manner. Thank you so much. Loved the article, it’s correlation with Yog darshan has made it even more relevant.

Thanks, Preeti, for the kind feedback. So nice to see that you found the article helpful. I am looking forward to your participation in the Samkhya study group starting tomorrow.

Sir can you explain different bhavanas and how many are there

Stella, I am not sure I understand the context of your question. In Samkhya there is mention of 8 “bhavas” of the intellect (buddhi). Four of these – dharma, jnana, aishvarya and vairagya are the result of sattva guna; their opposites – adharma, ajnana, anaishvarya and raga are caused by the guna tamas.

Was very useful samkhya philosophy explained very clearly.

Thank you sir.

Thanks, glad you enjoyed the article.

Really very deep notes I get from this link,thank you very much

It is aDiamond! A superb piece which summerises entire Hindu philosophy

Beginning with Shaddarshanas! Samkhya is transformed from Narikela paka to

Draksha paka. Thank uou sir.

Thanks, Jayanthi, for your kind feedback.

Namaste Subhashji, Thank you for undertaking this work. To understand Yoga one needs a firm foundation in Samkhya. I thank you deeply for your work, generosity and humility. 🙏Chandni

Chandni, thanks for the kind words. I appreciate your participation in the Study Group and enriching the discussion with your wisdom and knowledge.

Extremely clear explanation and written in an absolute concise manner, to the point yet descriptive. Very precise.